As graduation season approaches, international students at American universities find themselves immersed in a familiar spring ritual – not just studying for finals, but calculating visa timelines, getting new I-20s, and searching “OPT” on Google with increasing urgency. The Optional Practical Training program, which grants temporary though flexible work authorization to international graduates, has become something of an annual pilgrimage that thousands of foreign-born students make to try and remain in the United States. Data from Google Trends shows that interest in OPT spikes reliably in late March year after year, just as students begin finalizing post-graduation plans and confronting the reality that choosing to stay is signing up for a long-term struggle with immigration policy.

There really is no better place to see this phenomenon unfold than my home institution of Columbia University where roughly 40 percent of the student body hold non-U.S. passports. Chinese nationals alone make up more than 6,500 students and researchers – about one in five across the institution – most of them enrolled in graduate programs in the School of Engineering and Applied Science. The one-year Master of Science degree, in particular, has become a popular, self-funded track among international students, driven largely by the opportunity it offers to enter the OPT pipeline. In fact, as Adam Tooze observes, the school is so well known among China’s educated middle class that Columbia has earned a Mandarin nickname: 哥大 (gēdà), short for 哥伦比亚大学 (gēlúnbǐyà dàxué).

While still striking, these numbers feel like a holdover from an early-2000s ideal – when students came, studied, and stayed. They earned advanced degrees, joined U.S. research institutions, or took jobs at firms driving the next wave of innovation. For decades, this model helped power the American technological ecosystem, which leaned on foreign-born scientists to reliably staff its labs, launch startups, and support discovery. But the tides are shifting. Immigration barriers and political uncertainty have led a growing number of Chinese graduates in particular, to take their skills and return – often not as junior employees, but as lab directors, company founders, or venture-backed entrepreneurs. And crucially, where returning once meant catching up, now it often means competing.

This is not a trend that occurred by chance, and much of it instead is part of a collective push by the Chinese government to bring home the “sea turtles.” This term is a literal translation of the word haigui which is a linguistic play in Mandarin that emerged around 2002 as shorthand for overseas returnees. It is a homophone of 海归 (meaning “returning from overseas”) that employs the image of sea turtles that instinctively return to their birthplace to nest. But China’s success in reversing its brain drain has been anything but natural instinct. It represents perhaps one of the most coordinated attempts at talent repatriation in recent decades.

The foundations were first laid in 1978 when Deng Xiaoping urged sending students abroad and welcoming them back. By 1993, this evolved into an official Communist Party policy of granting “freedom to come and go” to overseas scholars. Since then, it has broadened from academic recruitment to a whole-of-government approach towards economic development. The scale of this shift is striking. Since the late 1970s, more than 6.5 million Chinese have returned after studying or working overseas. What began as a trickle became a wave: from fewer than 15,000 returnees in 2000 to over 580,000 in 2019. Today, more than 80% of Chinese who study abroad eventually return home. According to China’s Ministry of Education, by the end of 2019, 4.23 million out of 4.90 million overseas graduates had returned, a cumulative return rate of 86%.

Rather than playing to patriotism alone, the Chinese government developed an interlocking set of policies and incentives to make returning home not just possible but appealing. These measures range from national-level talent recruitment initiatives to localized perks, and they operate in tandem with reforms to institutional infrastructure and research environments. The centerpiece in this giant policy machinery is the Thousand Talents Plan that was launched in 2008. It provides competitive salaries, startup grants, and housing subsidies to lure top-tier researchers and entrepreneurs back from overseas. Its junior branch, Young Thousand Talents, targets scientists under 40, offering them fast-tracked positions and research independence rarely afforded to early-career academics elsewhere.

These national-level initiatives are reinforced by regional efforts that address logistical and financial barriers. Grants between $70,000 and $420,000, housing subsidies and tax breaks all reduce friction for returnees. Even China’s notorious household registration (hukou) system, which typically restricts access to urban benefits, has been modified. Chinese cities and provinces actively compete for this influx of overseas talent by offering fast-tracked hukou approval for those with foreign degrees, effectively removing one of the most significant barriers to geographic mobility within China. Degrees from prestigious Western universities provide automatic points in these systems, virtually guaranteeing residency rights in top-tier cities like Beijing and Shanghai.

Other local municipalities coordinate with state-owned enterprises and tech parks to offer further support. Although these programs in non-target cities have varying levels of success depending on the source describing them, I mention them here to demonstrate that there is consistent investment on all levels to lure back talent.

Importantly, the government’s efforts to encourage return migration have not relied solely on financial incentives. Structural reforms that address logistical burdens such as family resettlement, administrative complexity, and institutional rigidity have been equally instrumental. For example, China’s “double first-class” university initiative was launched in 2015 and has played a central role in this strategy. Universities designated as such receive concentrated state investment to develop “world-class” status (which has made them hotspots for recruitment in tech and bio), with policies emphasizing increased research and faculty productivity.

Thus, over the decades, we can see how the Communist Party’s organizational muscle helped make policy around returnees a main-stay pillar of the country’s national development strategy. In 2003, the Party formally declared itself the primary authority over all talent-related policies, creating the Central Leadership Group on Talent and integrating efforts across ministries, universities, and regions. This centralization allowed for rapid mobilization, especially during global economic downturns like the 2008 financial crisis, which China seized as an opportunity to bring its diaspora home – the director of China Service Center for Scholarly Exchange, Bai Zhangde explained in 2009 that:

“In terms of overseas students and scholar[s], the influence of the financial crisis is a mixed ‘blessing’...with the implementation of the domestic strategy of ‘rejuvenating the country through science and education’ and the strategy of ‘strengthening the country with talent,’ the adjustment of the country’s industrial structure and the acceleration of scientific and technological innovation have provided broad space and more opportunities for overseas students to return to China.”

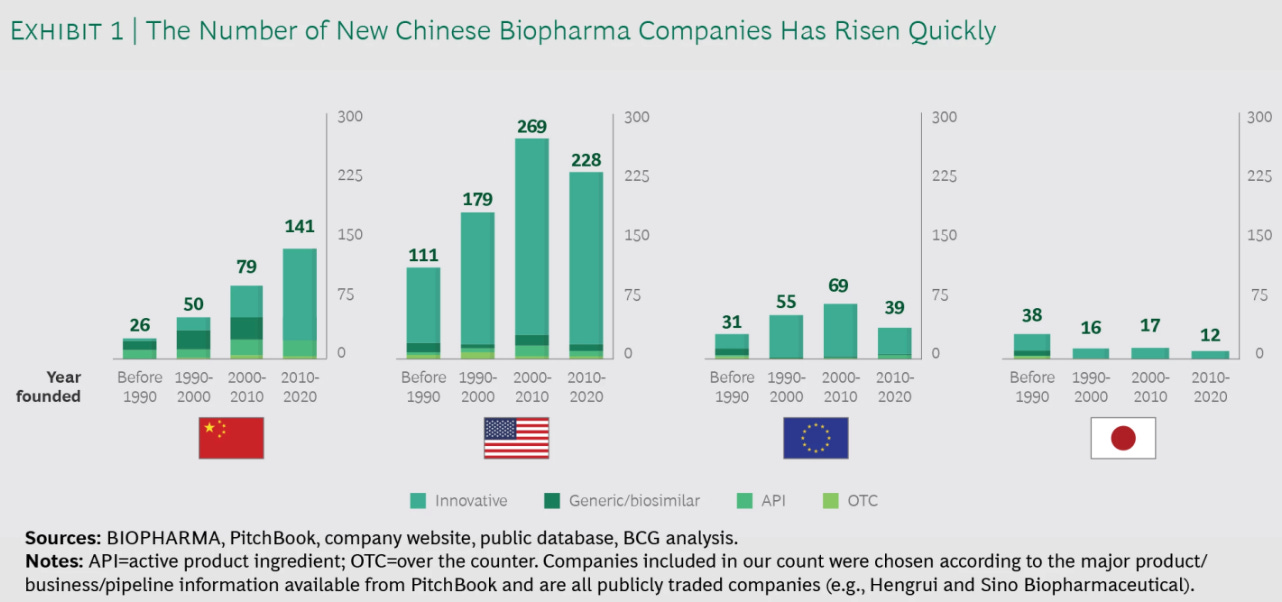

Nowhere has this push paid greater dividends than in biotechnology. Between 2010 and 2020, over 140 returnee-led biotech companies were founded in China, many by researchers trained in America in fields like oncology and gene therapy. Several of these firms – Biosion, EpimAb, and Harbour Biomed among them – have leveraged U.S.-acquired expertise to build drug discovery pipelines in China. The migration of this talent therefore reflects not only career incentives abroad, but gaps in the American system that make long-term retention harder than it should be.

The effects extend far beyond individual companies. A recent analysis found that participants in the Young Thousand Talents program significantly increased their research output after returning – publishing 27% more papers than their peers who stayed abroad, including more work in high-impact journals. These returnees also assume leadership roles at a higher rate, as indicated by a 144% increase in last-authored papers, suggesting they have independent labs and research agendas.

At the same time, China’s biopharmaceutical landscape has become more attractive for multinationals and global investors alike. Merck, for instance, recently acquired a preclinical GLP‑1 molecule from Hansoh Pharma, soon after rival Summit Therapeutics inked a partnership with a different Chinese company to develop a competitor to Merck’s blockbuster lung cancer drug. In fact, in just the first months of 2024, the ten most lucrative licensing and collaboration deals between Chinese firms and global pharmaceutical giants neared $26 billion in total value.

These developments reflect a broader reconfiguration of global innovation. China is now at par in areas like artificial intelligence and accounts for nearly one-fifth of all CRISPR-related patent families worldwide. In sum, it can be said that these trends reflect more than just individual career decisions; they signal a shifting center of gravity in global science.

In this new and volatile world order, America risks losing its scientific and technological edge not through dramatic collapse, but through quiet erosion. For one, immigration policy has not kept pace with the realities of global talent competition. The H-1B visa cap remains stuck at 1990s levels despite a vastly expanded economy and growing demand for STEM talent. And the transition from a student visa to permanent residency remains long and uncertain, often requiring years of employer sponsorship, which in turn limits mobility, discourages entrepreneurship, and deters risk-taking among early-career scientists.

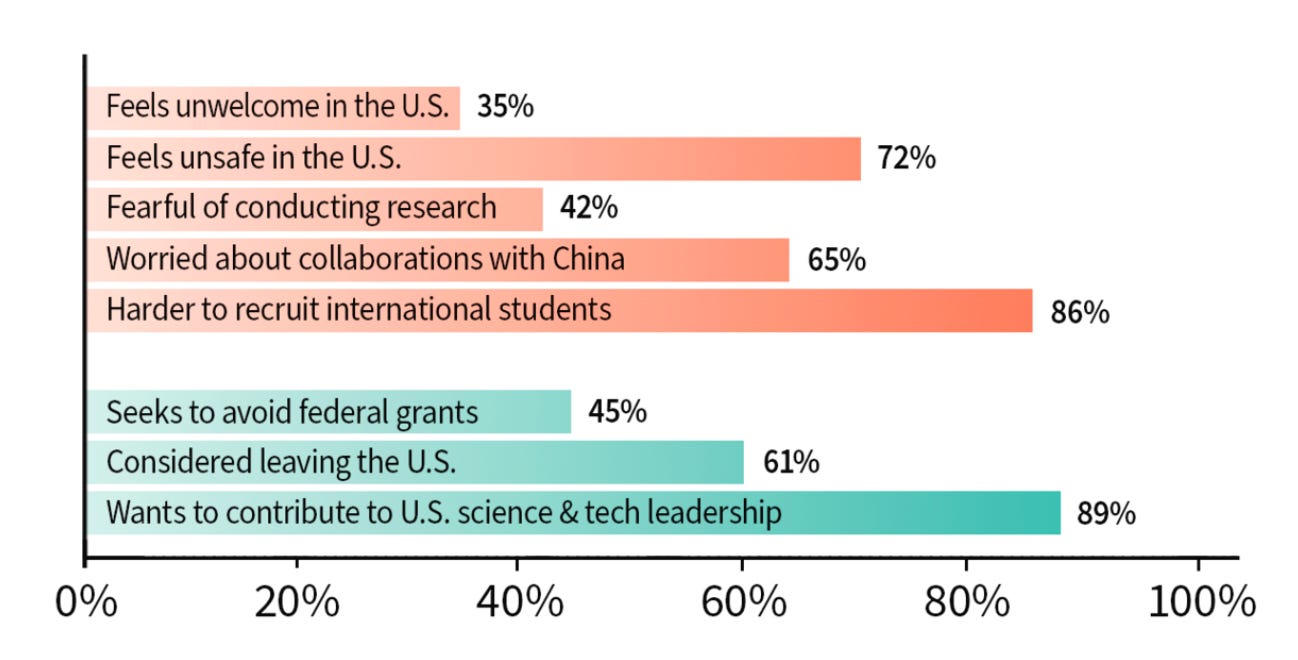

Compounding these structural issues are deeper cultural and geopolitical currents. For one, the now-defunct “China Initiative” created a climate of fear and suspicion that has yet to fully dissipate. A 2023 Stanford study found that the Initiative alone triggered a 75% jump in departures of China-born scientists from U.S. institutions. More than 1,400 Chinese researchers left between 2018 and 2021, and many others now avoid applying for federal grants out of fear or frustration.

To be clear, national security concerns about technology transfer are real and merit careful policy responses. But blunt instruments also have the capacity to produce unintended consequences. When highly trained scientists avoid grant applications that might fund breakthrough research, when promising graduate students choose other destinations for their education, or when talented faculty depart for opportunities elsewhere, the loss becomes material in very real ways.

Retaining global talent has long been one of America’s most formidable advantages. Chinese nationals alone account for 17% of all U.S. doctoral degrees in science and engineering, and historically, the vast majority (~75%) have stayed to work and teach in the U.S. after graduation – mostly to national benefit. But that pipeline is no longer guaranteed.

The shifting landscape demands at minimum a reconsideration of how the United States approaches global talent. This is not merely about competing with China’s incentive packages, which would be neither feasible nor necessarily desirable given different economic and political systems. Instead, America must leverage its existing position as a world-leader in training scientists, and make it easier for them to stay here (especially because researchers already want to).

There are some solutions. First, the U.S. could streamline pathways from graduate education to permanent residency, especially for STEM PhDs. Proposals to staple green cards to diplomas have circulated before; it might be time to offer this idea at least some consideration if nothing else. The annual cap on employment-based green cards (set at ~161,000 for FY2024) is not only inadequate but hampered further by per-country limits, and forces nationals of countries such as India and China into decade-long queues. These bottlenecks lead to significant attrition: when PhDs graduate into uncertainty, many return to their home countries. Modernizing the green card process by exempting STEM doctorates from annual caps or creating a fast-track system for graduates of American research institutions would be a concrete step toward retaining the very talent the country has already invested in training.

Second, federal funding agencies should specifically increase support for early-career researchers, providing the autonomy and resources that many now search for elsewhere. The median age at which researchers receive their first major NIH grant has risen to over 42, a striking lag given that many biomedical discoveries emerge from younger labs willing to take conceptual risks. As the Institute for Progress recommends, one promising solution is the expansion of postdoctoral and graduate fellowships that are institutionally portable, i.e awarded to individuals rather than tied to a particular lab and open to temporary visa holders. These reforms would make it easier for young scientists to move between institutions, form new collaborations, and launch independent careers, thereby unlocking “America’s latent scientific capacity.

Finally, the U.S. should treat talent retention as a matter of national competitiveness. That means integrating talent policy into broader strategies on industrial policy, research infrastructure, and immigration reform. It also means fixing problems that affect all researchers, such as administrative bloat, rigid academic hierarchies, and declining federal support for basic research. But it especially means recognizing that highly trained, mobile scientists have choices now that perhaps they did not historically. Therefore, ensuring that America remains “the best place in the world to do high-impact science” is no longer a self-maintaining status – it requires good legislation and a turn away from the current trajectory.

Despite the many challenges that students and researchers face in the U.S., for now, it remains the place to be. In writing the story of the “sea turtle” I aimed to not just make a point about China, but to remind that talent is mobile, and that systems shape decisions. America still has unmatched strengths in higher education and research (and these homegrown advantages need not be exported to foreign countries because of domestic policy inaction), but this clear upper-hand is eroding at the margins. Many international students would prefer to build careers in America if given a realistic path to do so – drawn by its universities and a culture of unfettered freedom. Yet, when that ambition meets structural friction, rational choices often lead them elsewhere.

This tide is not irreversible though and America can continue to be competitive by restoring clear blue waters for talented individuals from across the world.

With thanks to Samarth Jajoo and Adam Lehodey for feedback.

Lead image: William James Bennett. Weehawken from Turtle Grove. ca. 1830. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/13117.