A couple of years ago, my mother and I shared an inconsequential cup of chai on the roof of my house - a rare but fairly ordinary event. And while our conversation completely evades me, I vividly remember seeing clouds that day, fluffy and warm with edges dipped in syrupy golden hour sunshine. I was up there in the sticky summer heat till the sky grayed with nightfall, and I promised myself that tomorrow I would find the time to catch the sunset again. But the tomorrows became too warm, too sunny, too busy, too plain and the silent understanding of knowing that I won’t get to relive that feeling for the first-time all over again meant that the door to the roof remained shut.

Turns out this desire for novel, beautiful experiences is fairly abundant not only in you and I and the long aimless strolls we take, but in artists of the past who wanted to immortalize the intangible “air” of their surroundings in oil and crushed rock. Beyond just the act of capturing the moment, what set this group of people apart was their obsession with making the present special. Not aspiring to draw a vision of the utopian future as we do so often now, not reimagining mythical legends and classicized bodies to teach lessons using the past, but to show the present as something worthy in and of itself.

They rejected not only the painstakingly perfected artistic conventions of three dimensionality, linear perspective, composition, and idealized form (“painter dispenses with it [composition] to avoid falling prey to affectation and style”) but also radically gave way to a new series of art that served no purpose. There was no escapism, no publicly accepted coy eroticism, no education about the duties of living in society, nothing.

This meant that for a long time the Manets, Monets, and Morisots that we now so enthusiastically dedicate galleries to in museums, often found themselves headed straight to the reject/B-list salon exhibitions. Work deemed wholly unfit to share the stage with the fantasy and distance put together by more traditional painters.

Despite that, the impressionists were prolific and influential members of the artistic community drawing both infamy and praise across the social order. The most vocal among these voices was Stephane Mallarme - key to literary symbolism, the written counterpart to impressionism, and Manet’s close friend. It is through his contemporary defense of the radical pursuit of representing the truth that we catch a glimpse into the philosophical basis of artistic modernity.

Modernity that was steeped in the idea of “the pleasure we derive from the representation of the present is due not only to the beauty with which it can be invested, but also to its essential quality of being present.” This quote from a series of essays by Charles Baudelaire, a poet at the height of his career and at the fringe beginnings of symbolism, exemplifies the general notions of thought that surrounded artistic evolution.

Art was to become an organic extension of sight, a tool to behold “the delight that we should experience could we but see them [objects] for the first time.” And what better way to imbue the paintings with an aura of authenticity and presence than to move out of the studio, do away with the whims of imagination, and instead draw in open air?

This idea of en-plein-air became the most lasting legacy of the impressionist movement -- nature was pure, true, and unadulterated, and the responsibility of the artist was to “let the hand and eye do what they will, and thus through them, [nature will] reveal herself.”

Plein-air loosely translates to the outdoors or the theory of open air which talks about the effect the atmosphere creates with a specific focus on the way in which complexions change. The idea is that light is reflected and broken as it interacts with space, thus “discoloring the flesh” and creating inherent beauty of its own rather than carefully staged “artificial glories” generated by the imposition of candlelight. Natural sunlight also softens the lines, blurs the figures, and its interaction with solid objects creates subtle dynamism.

Besides practical aesthetics, plein-air also embodies the philosophical pursuit of artists being truthful in their depictions. As Mallarme put it, being real means “to adopt air almost exclusively as their medium.”

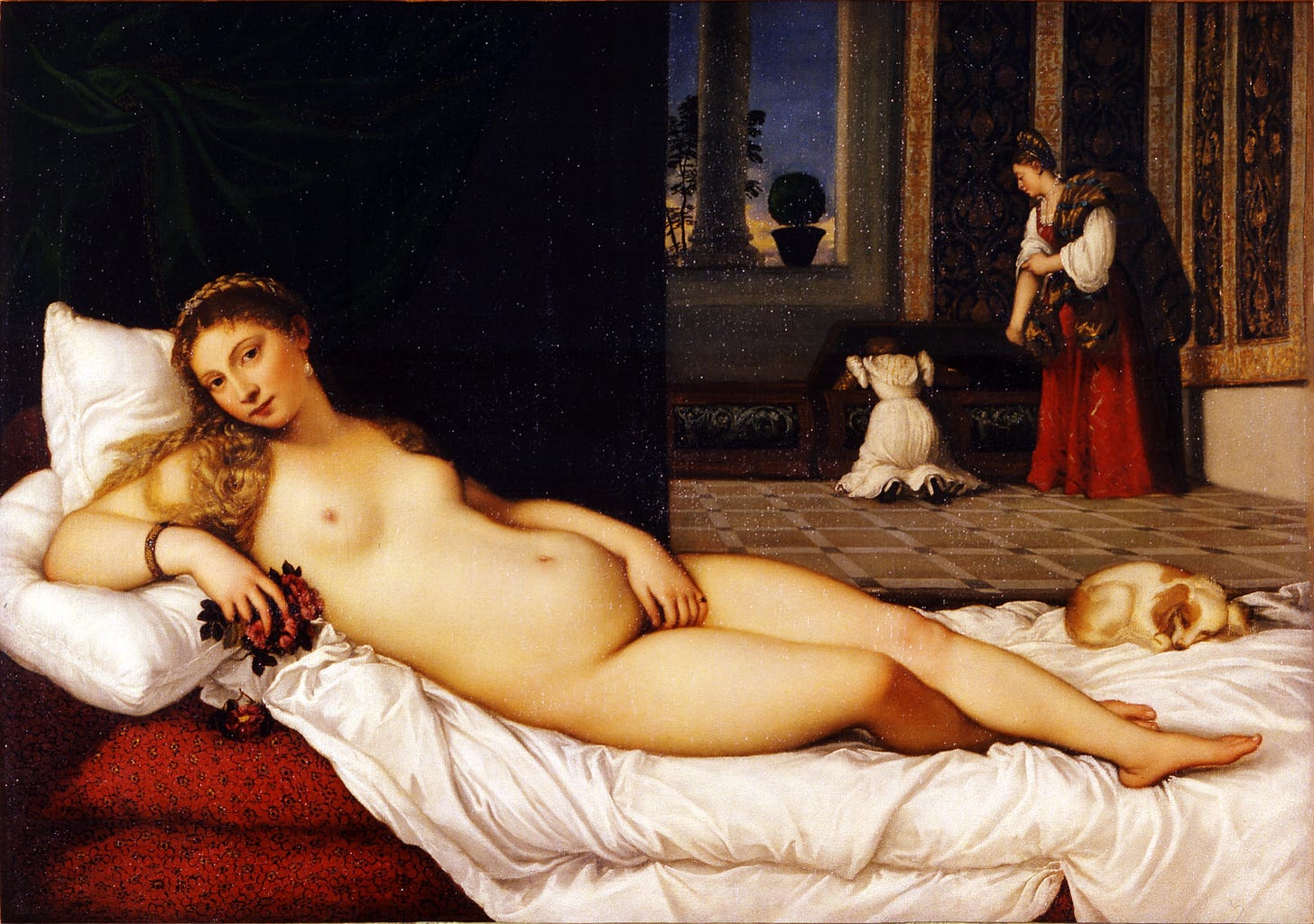

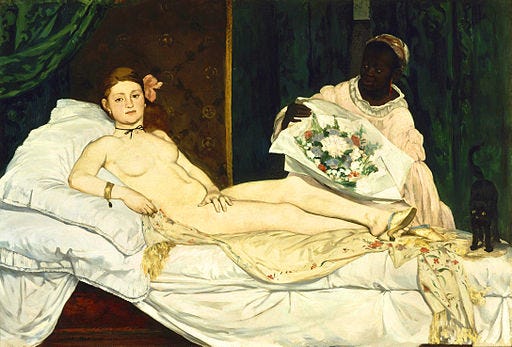

A very good example of this is the notoriously infamous painting of 1865 by Manet titled Olympia -- partly because it functions as the reference point to impressionism as a whole, and partly because it is inspired by and thus can be compared to classicized renaissance art. On the top we see Titian’s version of a seductive goddess in a relaxed, inviting pose, her skin glowing with divine light, feeding into the fantasy of the male gaze. In contrast, Manet’s version on the bottom shows a stiff, tense, defiant sex worker with grayish skin and an active gaze that stares directly at the viewer. The lack of allegory lays bare the transactional nature of prostitution and the realities of society that painting’s affluent audience chooses to ignore.

The deeper color palette, the visible brushstrokes, the sharp outlines of the figures are all stylistic choices by Manet that make the art real -- to say that this is how the eye views the scene, and that people put in labor to make the world work the way it does. However, as Baudelair put it, “if our latter day art is less glorious, intense, and rich, it is not without the compensation of truth, simplicity, and childlike charm.”

As a newsletter that wants to try and find the stories hidden in everyday observations, I thought that looking at the first cultural proponents of the idea of “mundane beauty” might be an interesting exercise. Manet and other artists of his style seem to be able to evoke a sense of wonder with their work not because they were constantly surrounded by extraordinary sights but because they chose to see them. Just like you and I can choose to return to that rooftop with a cup of chai every evening, choose to pull ephemeral stories from our routine yet incredible lives.

A lot of the ideas in this essay are thanks to my art history professor last semester, Dr. Caitlin Meehye Beach, who sent me a really great set of references to work with. I am very grateful for her guidance and the class she taught!

References

Mallarmé, Stéphane. "The Impressionists and Edouard Manet." Modern art and modernism: A critical anthology. Routledge, 2018. 39-44.

Baudelaire, Charles. "The painter of modern life." Modern art and modernism: A critical anthology. Routledge, 2018. 23-28.

“Manet and Mallarmé.” Philadelphia Museum of Art Bulletin, vol. 62, no. 293, 1967, pp. 213–34. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/3795193. Accessed 5 June 2023.

By Titian - bQGS8pnP5vr2Jg — Google Arts & Culture, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=13523024

Édouard Manet, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons